Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 59:00 — 138.7MB)

Subscribe: RSS

patreon campaign progress report:

111 patrons (no change)

53% towards our goal (no change)

want to help? http://www.patreon.com/frameworkradio

this edition of framework:afield has been produced in the uk by kevin winser. an online release version of this work can be found here: https://infectedsenses.bandcamp.com/album/january-the-9th-2021. producer’s notes:

This is a collection of field recordings all gathered on the same day, Saturday, January the 9th, 2021 during a social lockdown in Exeter, UK, due to the Coronavirus pandemic. It was also my birthday, so there was both personal and wider social context.

Made as part of the field recording module on my MA in sound art, the recordings were made using the Zoom H2n, to WAV. I knew that I would be most interested in spatial capture rather than isolated sounds, so the device setting was for a 2-channel surround (2.1) utilising all five of the microphone capsules. I had hoped to use and experiment with other microphones, but access to Uni assets was prohibited for reasons of geography and Covid-19 restrictions. This lockdown also meant a change to my initial proposal of capturing sounds from a wider source in ‘The Third Place’, such as restaurants and pubs. Much of the day’s recording was obviously to be within the relatively controlled environments of my house, with the microphone placed within the given ‘scene’ of the bathroom, kitchen, or front room.

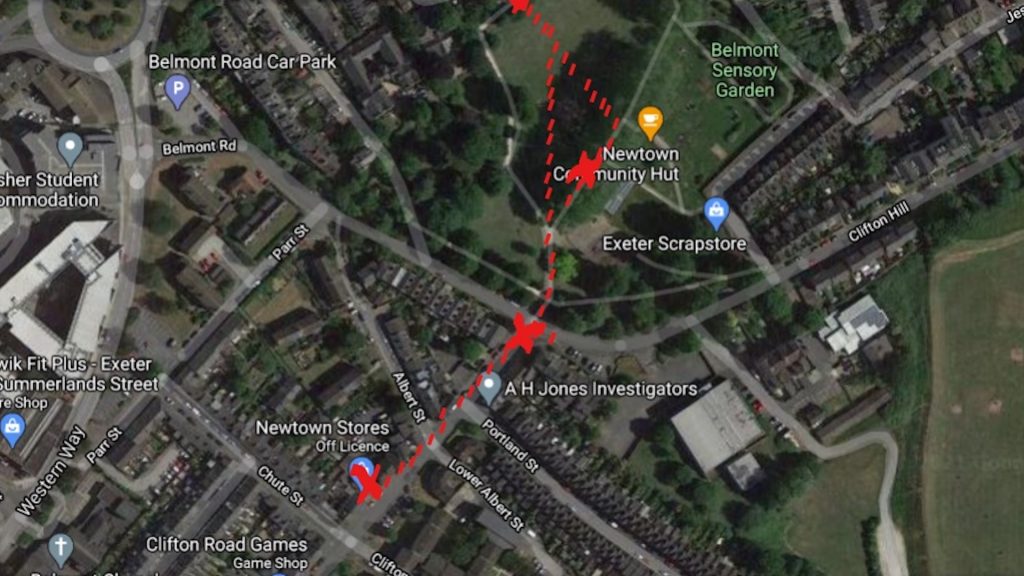

The other external locations, in the local park, outside my house and the cornershop, were less controlled sound environments than the interiors but as the nature of what I intended to capture was ‘the everyday’ as it happened and not to make an industry-standard, sound library as such, I was happy to place the microphone anywhere stable and just let life happen around it.

Having engaged with The Sounds of the Pandemic, an International online conference organised by the University of Florence in December 2020, I knew I wanted to go to the city high street to capture what I thought would be the relative ‘sound of silence’ there, compared to a non-lockdown situation. I decided to walk the length of two streets with the mic handheld, although in retrospect, I now think I ought to have decided on a single location for it.

It offers a chronology of recordings that I think operates within and intersects various ‘field recording’ schools of thought, sub-genres, debates, and concerns. Soundscape, sound walks, a sense of place, ‘boring’, everyday sounds and casual conversation, audio diary, informal storytelling, self-reflexive narrative, and (micro)social history and sound heritage.

I was aware of the requirement to produce technically acceptable recordings within the context of this module and within the traditional phonographic practice of the objective of ‘neutral’ field recording and sound capture principles of acoustic ecology but also given my background in radio broadcast, oral history, and heritage projects and informed by certain fields of thought within my first degree of Cultural Studies, I wanted to include some element of storytelling and documentary.

Drever considers field recording as originating not only from the work of pioneers of the 1960s such as the World Soundscape Project, Luc Ferrari, and Bernie Krause but also from much earlier precedents. Phonographers and sound archivists such as Ludwig Koch, Humphrey Jennings and the GPO Film Unit.

Another influence I was aware of was from the sound walks of Hildegard Westerkamp, where she places herself within the sonic landscape with spoken and ‘self-reflective narrative’ to create an ‘autotopographic’ sound work about her relationship with the environment. Westerkamp’s narrative is overdubbed in the studio, and as is mine is contained within the recordings where speech events happen and also a la Westerkamp.

The third influence was from the more recent, Sound Diaries project by The Sonic Arts Research Unit at Oxford Brookes University. The project explores what it means to record life in sound as Auditory archaeology and to acknowledge the ‘boring’ and mundane as potential sonic time capsules.

“It’s always exciting to hear someone documenting their daily lives in sound – and rarer than you might think given the technologies that we now have so readily available.”

kevin winser, 2022.02